We busted the MYTH that milkfish don’t produce lactic acid as the reason why they fight for so long

This post was created in collaboration with the Alphonse Fishing Company, Blue Safari, and Alphonse Foundation and a similar post can be found here. The study was conducted thanks to a grant from the Alphonse Foundation, Alphonse Fishing Company, and Blue Safari, and in partnership with the Island Conservation Society, University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Carleton University.

Dr. Andy Danylchuk, Dr. Luke Griffin, Dr. Steven Cooke, Dr. Michael Lawrence, and Sascha Clark Danylchuk

Every few months there is a post in social media remarking that milkfish (Chanos chanos) can fight for so long on the end of a fly rod because they do not produce lactic acid. Sometimes it’s even attributed to their diet, which mainly consists of algae. Lactic acid is a byproduct of anerobic muscle activity and is what causes muscles to cramp up after strenuous exercise, ultimately making them harder to use (like when exerting yourself during a long running race). This is a common physiological response in vertebrates (and has nothing to do with diet), so, as scientists, we were always quite perplexed by the notion that milkfish may somehow be an exception. In general, understanding how fish physiologically respond to capture and handling is important, and a great step towards developing science-based best practices for catch-and-release.

Thanks to the request for us to lead the project and a grant from the Alphonse Foundation, Alphonse Fishing Company, and Blue Safari, we recently partnered up with this team and the Island Conservation Society, University of Massaschusetts Amherst, and Carleton University in the Seychelles to see if milkfish produce and build up lactic acid as they fight. Lactic acid ends up in the blood as lactate (as a means to metabolize or get rid of it), and is something that we are able to measure in the field.

With the weather gods looking out for us and with ample milkfish working the foam lines of the outgoing tides just offshore of the reef crest of St. Francois Atoll, and dropping off the flats inside the lagoon, our collective team of guides and anglers managed to fight and land enough milkfish across a range of fight times to test this hypothesis. Using non-lethal blood sampling after the milkfish were landed, along with portable blood lactate meters, we tested the blood for the concentration of lactate.

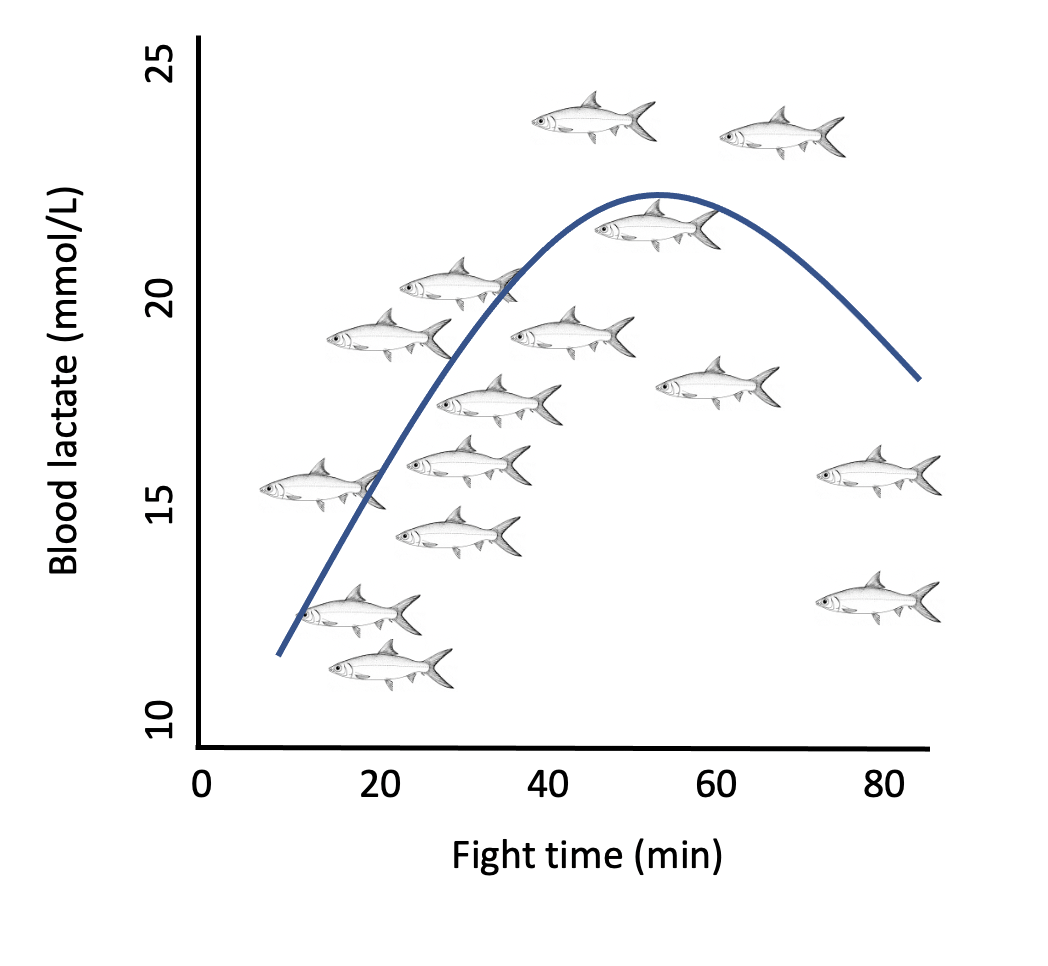

And, what we can safely say is, the myth is busted. Milkfish produce lactic acid and blood lactate and the concentrations of it increased with fight time. However, what we discovered is that for fight times greater than an hour, blood lactate in some fish started to decrease. This is not something we typically see in other fish species. Why this happens is still a bit of a mystery, but it could be because of milkfish’s ability to move a TON of water over their gills, helping them begin to recover from the burst swimming earlier in the fight — i.e. these fish might be so efficient at respiring (“breathing”) that they can start to recover while they are still fighting.

Final Words

What this short study showed is that milkfish do build up lactic acid and blood lactate as they fight on the end of a fishing line. Given that it did increase within the first hour, and that higher blood lactate levels can impair muscle activity and the potential for milkfish to get back to feeding on foam lines and avoid predators, we suggest that a species-specific best practices for milkfish would to be to keep fight times to less than 20-30 minutes. Until the rest of the capture and handling data is analyzed, we also encourage that anglers continue to follow Keep Fish Wet Principles and Tips.